- Aman, Student, Jharkhand

The grandeur of Red Brick Lady Irwin Hospital in Ranchi has increased manifold now bustling with activities. This lady Irwin Hospital was established in 1933 as the only gynaecological and obstetric hospital of Chhota Nagpur. Later this was popularly known as Birla Hospital as about 210 acres of land were donated by the Birla group. Since that time, the hospital had been the only hope for the poor and tribal population of this area, especially for maternity related medical help. As time elapsed, this transformed into a general hospital, especially for treatment of rabies, tuberculosis, minor injuries and other common diseases.

However, in mid-2014, the Jharkhand government had announced a plan that would have majorly impacted on of one of the state’s largest public hospitals. The proposal was to privatise major services of Ranchi Sadar Hospital (RIMS) through a Public–Private Partnership (PPP). On paper, the plan promised efficiency and modernisation. But for ordinary people, activists, and health workers, it raised immediate alarm: would the majority of lower income people still have access to affordable treatment, or would public healthcare be handed over to corporate control?

The ‘Problematic Privatisation Proposal’ (PPP)

The proposal came from the BJP regime, headed by CM Raghubar Das in 2014, in collaboration with the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the private-sector investment arm of the World Bank. It envisaged outsourcing diagnostic services, pathology labs, and several non-clinical operations to private companies under a Public- Private Partnership model. The logic given was familiar: private investment would bring in better facilities, reduce delays, and improve management. Yet activists pointed out that such privatisation usually leads to higher costs of care, exclusion of low-income groups, and major reduction of social accountability.

In fact, the International Finance Corporation (IFC) had listed Ranchi Sadar Hospital on its website as a PPP to be promoted. IFC was formally appointed as the transaction advisor for the project, with the role of planning the transaction, marketing the proposal, drafting bid documents, and assisting the government throughout the bidding process until the contract was awarded. A blueprint was prepared for a Rs. 100 crore project on a public-private partnership between the state government of Jharkhand and private health corporations. Soon, CEOs of Medanta, Apollo and Escort, etc. rushed to Ranchi for a tie-up. In other words, this was a carefully prepared plan by the World Bank agency to hand over management of Ranchi’s key public hospital to corporate players, and Medanta was reported to be interested.

Rise of people’s resistance

Various social organisations in Ranchi realised the dangers of this major handover. Ranchi Sadar Hospital is not an ordinary health facility; it’s a lifeline for thousands of poor and marginalised patients from across Jharkhand. Turning it into a privatised entity would put essential care out of reach for those who could not afford corporate hospital fees. Several civil society organisations, people’s science organisations, women, youth and tribal associations, craft and trade unions, street vendors, doctors, paramedics, political parties and several intellectuals like P.P. Verma, Father Stan Swamy, Prof. Prabhat Singh, Dayamani Barla and Dr. Karuna Jha etc. opposed the government move of privatisation of the Sadar hospital, which was giving the free medical facilities to the common people.

These wide range of organisations and individuals, including Jan Swasthya Abhiyan, joined hands and a joint platform was formed to save the government-run Sadar Hospital from privatisation under the name of “Sadar Aspatal Bachao Aandolan”.

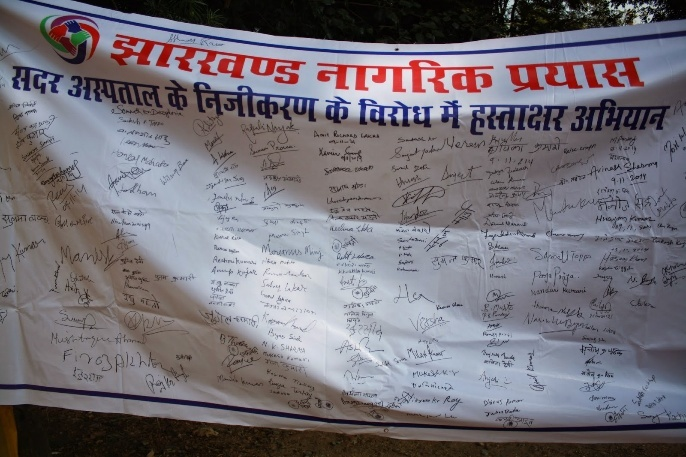

This caught the imagination of common people who started participating in the protest action of this platform. Organisations like Jharkhand Nagrik Prayas, Jharkhand Science Forum, Science for Society, Bharat Gyan Vigyan Samiti, Health association workers, BSSR (Medical Representatives), and the Indian Medical Association. Some of the political parties like SUCI, CPI, CPI(M), RJD, Samajwadi activists and several tribal leaders and organisations supported the movement. Many educational institutions such as XISS, also backed the movement. Petitions and representations were given to the Governor, Chief Minister and health secretary of Jharkhand. However as usual, the administration practised their delay tactics.

The first publicly organised step of resistance came on 28 July 2014, when this platform submitted a memorandum to the Chief Minister. The memorandum clearly opposed the proposed handover of the hospital to private interests, and argued that the hospital must remain under government management.

Following this, on 3 August 2014, a signature campaign was launched at Firayalal Chowk, one of Ranchi’s busiest squares. This was a visible, public campaign which invited thousands of ordinary people to sign their names against the privatisation move. The campaign gathered momentum, spreading awareness across the city that something important was being decided about their hospital without their consent.

Soon after, activities such as street meetings, pamphlet distributions, and public actions were undertaken. By October and November 2014, protests were taking place at multiple sites in Ranchi, including near the hospital itself and at the Jharkhand Assembly. Prabhat Khabar and Dainik Bhaskar reported on demonstrations where activists held placards warning against PPP, explaining to people that privatisation would mean higher charges and fewer free services.

Broad based unity takes the movement forward

The movement was based on a wide range of social, political organisations and groups including activists from various Left and Socialist parties and groups, factions of JMM, Jan Swasthya Abhiyan (JSA),Right to Food Campaign, Adivasi organisations, advocates, college faculty, doctors and student unions. It is important that Healthcare employees of RIMS Hospital including nurses and government doctors also publicly opposed the move, fearing job losses and the loss of professional livelihood under corporate management. This broad based social-political coalition was a critical factor in expanding the movement, which expressed people’s concerns cutting across social, political, and professional lines.

The campaign moved forward with further waves of protests, and in June 2015 a delegation met the Governor of Jharkhand to press their demands. The demand was that all departments of Sadar Hospital should remain government-run, bed capacity must be increased, and the state should strengthen the hospital rather than privatise and weaken it through PPP.

Another dharna held in June 2015 raised an 8-point demand charter, again emphasising the need for public management. News reports at the time noted that although the government had earlier announced the PPP decision, “no formal process” to hand over the hospital had actually taken place. This was a clear sign that the continuous public pressure was having its intended effect: the plan for privatisation was halted. A spree of Basti, mohalla campaign, signature campaign, protest demonstration and dharna started mounting pressure on the state government to reverse the decision of privatisation.

Coincidentally, a local philanthropic businessperson supplying construction materials and hardware lodged a public interest litigation in the state high court against the state government’s move of privatisation, though he had some personal financial interests in this issue. The Sadar Hospital Bachao Andolan took it as an opportunity to intervene. The Chairman of Ranchi Citizens Forum, Adv M.K. Habib, an eminent lawyer, advised Dr. Prabhat Singh, the secretary of Ranchi Citizens Forum, to become an intervenor in this PIL in Jharkhand High Court. Adv Jayant Pandey, under the guidance of Adv M.K. Habib, pursued the legal interest of Sadar Hospital Bachao Andolan. The intervenor presented a bulk of documents to prove that a partnership with Health corporations like Medanta, Apollo and Escorts will escalate the medical expenses of common people, and the provision of free medical treatment will cease.

Comparative data was provided to prove that such an arrangement will be costlier than any other private hospital in Jharkhand. This arrangement of privatisation could have ignored the primary treatment of common diseases and could have focused on specialised, costly treatment. This legal battle turned into a surprise when the honourable court ignored the primary PIL, and Dr Prabhat Singh’s intervention became the main legal question. The Health Secretary and the respected health minister were summoned by the court. Adv M.K. Habib’s arguments and the documents of the public protest were duly considered favourably by the court. The Raghubar Das-led state government and IFC could not contradict the strong documentary evidence.

A people’s victory

The court directed the state government to cancel the privatisation proposals and to take up the responsibility of fulfilling all the obligations mentioned in the contract. This included developing a modern public hospital with facility of 500 beds with OPD, and also making arrangements for 50 medical seats and 200 paramedical seats.

The Jharkhand government retreated and the Health Minister publicly assured that no privatisation would be carried out without public consensus. The proposal and drive for privatisation by World Bank – IFC was decisively pushed back by the force of the people’s movement. Ranchi’s largest public hospital remained in government hands.

The policy push for privatisation of healthcare in India is currently being actively pushed by powerful international and national forces, including the World Bank. However, as this remarkable story of the anti-privatisation movement from Ranchi shows, if a broad range of people are organised and mobilised, even governments and major international agencies can be pushed back, and privatisation can be halted. The Ranchi Sadar Hospital campaign showed what ordinary people can achieve through simple but powerful tools: memorandum, signature campaigns, street meetings, dharnas, legal interventions, delegations, and sustained follow-up.

Today, the glory of Irwin Hospital has come back as a full-fledged 500-bed hospital, and 20 seats for PG in Gynaecology and Obstetrics have been added as an extension of RIMS. This Sadar hospital movement gave birth to Jharkhand Swasthya Abhiyan (JSA), all participants of this Sadar hospital movement merged into this platform. A people’s health charter of Jharkhand was formulated and presented to the Jharkhand Governor, Smt. Draupadi Murmu during that time, who favourably responded to this policy.

As the Jharkhand State government is again planning to privatise six district hospitals in PPP mode, Jan Swasthya Abhiyan – Jharkhand has decided to launch a state-wide campaign to oppose this move. On 3rd August, 2025, various associates of JSA Jharkhand met and decided to develop a strong movement to stop the privatisation of government hospitals. A protest committee has been formed to protest and defeat the state government’s move of privatisation. JSA Jharkhand is confident that once again, the people of Jharkhand will defeat the nefarious move for privatisation of healthcare in Jharkhand.

Power to the people!

Inspiring story